The Git Etiquette

Developers sometimes feel overwhelmed with possibilities given by modern distributed version control systems such as git. Countless methods of merging (squash, rebase, vanilla), switches, workflows, pull requests etc. may as well make you want to go back to good ‘ol SVN. And that’s the trend I often observe when introducing git to developers.

Git offers many flags/switches to make it behave more like the familiar SVN. But the question arises whether using these flags to make it look like SVN is actually the way to go?

What I’m describing below is a set of guidelines that will allow you to simply love git - it’s all in understanding how the thing really works.

One such flag is the git merge --no-ff which disables git fast forward. The reason people

advice on using it, is to keep your history non-linear so supposedly you can easily cherry-pick branches and know exactly

was was going on just by looking at the repo graph… NO! It all looks rosy before you start digging into it. I always

assume that people able to write tools like git are much ‘cleverer’ than I will ever be, so who am I to question their

decisions? Same happens here. Fast-forward is one of the most prominent git features, so why, oh why would we want to

disable it?

Well we don’t, we don’t because --no-ff breaks bisect blame - as simple as that. The exact reason that prompted you

to go for --no-ff for easier history tracking has now robbed you of a way to quickly find bugs with git bisect.

Surely that isn’t what you wanted?

Rather than non-linear history, what you really want is a stable history, one where each commit on your master is a potential

release candidate. Getting to this point is relatively simple. All that’s required is your team to be disciplined. The usual

problem with discipline when working with SVN was that you were simply not allowed so called checkpoint commits. A

checkpoint commit is one that you make half way through any logical piece of code. You do it because you need to backup

your work, or want to do some work from home so you need a way of hosting your code somewhere. Problem with checkpoint commits is

that they represent unstable state of your code, those commits can’t be safely reverted to and rolled to production because

they are not ready - and this is the reason that is being given as the main motivator for merging feature branches with --no-ff flag - isolation of non completed work.

While the reasoning is absolutely correct, the solution still isn’t. We do not want to use --no-ff. What we want is a clean

linear history we feel comfortable with.

Both things seem to contradict each other, how can possibly the value of checkpoint commits be kept without ruining the shiny commit history you were working on so hard? Simple… commit history in not the sacred un-mutable creature we know from SVN - not as long as you didn’t push it to remote.

Here, the concept of remote/local branches comes to it’s full potential. You should feel absolutely fine about rewriting your local history. Who cares if you do? At the end of it, your branch tip will be in exactly the same place, files will be changed in the same way. It’s the description of how you got there that changes - if you can prepare your branch history in a way that is logical and easy to follow by your colleagues - by all means, do that!

Before I get to the proposed workflow, a word (or few) on commit messages…

- make sure you are concise within the short commit message;

- don’t use the

-mswitch, use the editor; - reference the bug/card number in your commit so modern tools like Github Issues or Jira can track your commits back to tasks;

- agree on a common format and use it;

- at all times think about the code review that is to follow;

- be verbose with the long commit message - use it to motivate why you did the changes you did;

--patchcommits are absolutely fine, use whenever it makes sense (that goes especially towards html/css developers).

Let’s have a look at typical feature branch workflow without the now popular develop branch. We branch from master to do work and we only merge back when work is done.

Consider following:

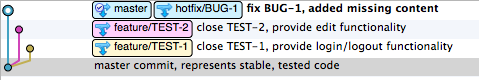

We have a master branch which holds only stable tested commits, the idea is that we can rollback to any of these commits and be confident about it.

We have 2 feature branches, both created from stable master. Those branches represent logical bits of work (stories, cards, bugs).

We have a hotfix branch used to fix bug found in production that has been merged into master.

The graph looks something like below

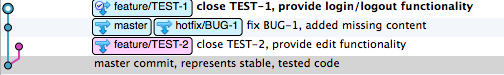

Now, to reflect the fixed bug in the development branch we can rebase the branch to get everything up to date. Let’s do it on TEST-1.

git checkout release/TEST-1

git rebase master

Nice, clean, linear. We know exactly what happened and when. All tests are passing. Because we tested after rebasing, we know it is absolutely safe to merge. Let’s do it (I will also clear the BUG-1 as it’s been merged before and it’s not needed).

git merge feature/TEST-1

git branch -D hotfix/BUG-1

git branch -D feature/TEST-1

Again, nice and clear. If we were to rollback to any commit we are now able to say what exactly changed in that commit and if a bug was introduced, git bisect

is more than happy to help whenever we need it.

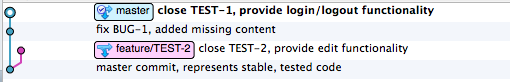

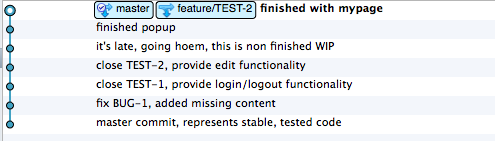

So, all good, but the TEST-2 feature does not pass through QA. We needed to make further changes, go home in the middle, made few silly commits and have created a bit messy history. Something like below…

Typos, work half done, checkpoint commits, all the things that make developer comfortable but are a killer to your clean linear master history.

Oh noes!

If we were to rebase our branch now, and merge it with fast-forward into master, the resulting tree is somewhat ugly, definitely not one where we are confident all changes are stable.

This is definitely not the way to go.

Remember when I mentioned that it is alright to rewrite history? The time-space continuum will be fine as long as you didn’t push changes, Marty and Doc can breath easy.

git rebase --interactive master - is what you need at this stage. Simply putting, git will read through your commit

history, create a list of changes and politely ask you what you want to do with them.

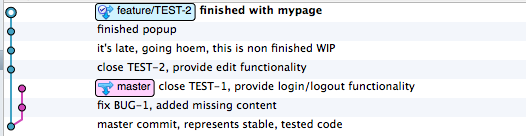

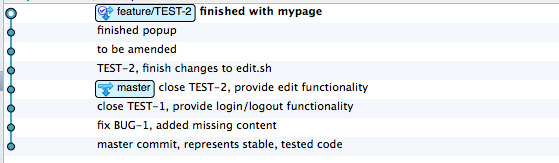

Current working tree on TEST-2 looks something similar to

edit.sh edit_popup.sh file1 login.sh logout.sh mypage.sh

Files touched by TEST-2 branch are edit.sh, edit_popup.sh and mypage.sh. Commits, however, are somewhat messed up

because we did not use logical separation. First commit was for changes in edit.sh and newly created edit_popup.sh,

then the following one further modified edit_popup.sh and last commit added mypage.sh

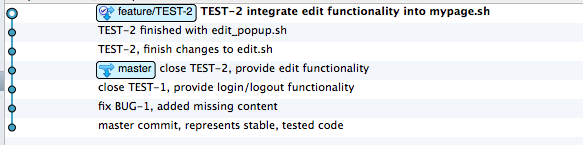

Ideally, we want to split the first commit so it only applies to edit.sh, then we want to merge the remainder of that commit

with next one so changes to edit_popup.sh are within single commit. The last commit is nice and clean so we leave it be. We

want to provide some more meaningful commit messages too.

Let’s rebase interactively.

git rebase -i masterpick 23d0d39 it's late, going hoem, this is non finished WIP pick f36ce29 finished popup pick 478d6ca finished with mypage # Rebase 6e8f772..478d6ca onto 6e8f772 # # Commands: # p, pick = use commit # r, reword = use commit, but edit the commit message # e, edit = use commit, but stop for amending # s, squash = use commit, but meld into previous commit # f, fixup = like "squash", but discard this commit's log message # x, exec = run command (the rest of the line) using shell # # These lines can be re-ordered; they are executed from top to bottom. # # If you remove a line here THAT COMMIT WILL BE LOST. # # However, if you remove everything, the rebase will be aborted. # # Note that empty commits are commented out

What you see above is the list of commits in chronological order. Using the instructions below you can rewrite history.

The last commit message is great, will leave it at pick because there is no point changing that.

First one needs changing, log message is crap and indexed files need changing - flick command to edit.

Will deal with the second commit later.

Save and quit.

Stopped at 23d0d39... it's late, going hoem, this is non finished WIP You can amend the commit now, with git commit --amend Once you are satisfied with your changes, run git rebase --continue # rebase in progress; onto 6e8f772 # You are currently editing a commit while rebasing branch 'feature/TEST-2' on '6e8f772'. # (use "git commit --amend" to amend the current commit) # (use "git rebase --continue" once you are satisfied with your changes) # nothing to commit, working directory clean

Output is quite self explanatory, what we want is to reset our index to be able to work with that commit.

Let’s take index back one commit.

git reset HEAD~1

git status# rebase in progress; onto 6e8f772 # You are currently splitting a commit while rebasing branch 'feature/TEST-2' on '6e8f772'. # (Once your working directory is clean, run "git rebase --continue") # # Changes not staged for commit: # (use "git add <file>..." to update what will be committed) # (use "git checkout -- <file>..." to discard changes in working directory) # # modified: edit.sh # # Untracked files: # (use "git add <file>..." to include in what will be committed) # # edit_popup.sh no changes added to commit (use "git add" and/or "git commit -a")

We can now commit the edit.sh file separately to edit_popup.sh to encapsulate changes a little bit better.

Continue with git rebase --continue

When all is done our history looks a little better

All is left to fix is that unnecessary double commit regarding edit_popup.sh

git rebase --interactive master

Make following changes to the file:

pick 11d959c TEST-2, finish changes to edit.sh reword 0d005ba TEST-2 fixup ba7dd68 reword c1b795b TEST-2 # Rebase 6e8f772..c1b795b onto 6e8f772 # # Commands: # p, pick = use commit # r, reword = use commit, but edit the commit message # e, edit = use commit, but stop for amending # s, squash = use commit, but meld into previous commit # f, fixup = like "squash", but discard this commit's log message # x, exec = run command (the rest of the line) using shell # # These lines can be re-ordered; they are executed from top to bottom. # # If you remove a line here THAT COMMIT WILL BE LOST. # # However, if you remove everything, the rebase will be aborted. # # Note that empty commits are commented out

Save and quit.

What we end up with, is a clear history of our branch work.

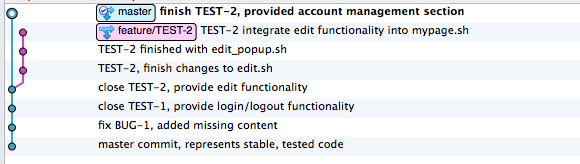

There are further choices from here onwards. If your branch was long lived, has plenty of clean commits, each of these commits represent a logical state to which you can rollback you can simply integrate it into your master (or develop).

If (after all this hard work rebasing) you decide that the branch isn’t big enough to deserve separate commits in your master (this is the likely option) you can use a squashed merge to represent it as one in master.

To squash merge all you need to do is merge onto master

git checkout master git merge --squash feature/TEST-2

Git will move the patch of you changes on top of your master as a single commit

git status

# On branch master # Changes to be committed: # (use "git reset HEAD <file>..." to unstage) # # modified: edit.sh # new file: edit_popup.sh # new file: mypage.sh #

You can now commit into master/develop as a single piece of work.

This approach is great for short lived branches on small projects, but it does have problems. It’s fine if you are the person merging that code into master as you are 100% sure you will merge the history correctly and that your name will be on the blame. But by doing this you are bypassing the entire code review cycle.

Squashing your feature branch down to one commit (if it’s short lived) and then creating a pull request to master is the preferable approach as it fits better into code review workflow.

When all work is done, the repo history looks very simple, there’s no need to keep it non-linear and it’s easy to revert or to branch of at specific point.

You can remove the now integrated branch feature/TEST-2 and enjoy life, glory and lack of abuse from your co-devs.